Day #7

Antarctica in the Fog of the Pandemic

There’s a saying that goes, “A wise person climbs Mount Fuji once; only a fool climbs it twice.” I don’t want to know the saying about someone who has gone to Antarctica six times, as I now have.

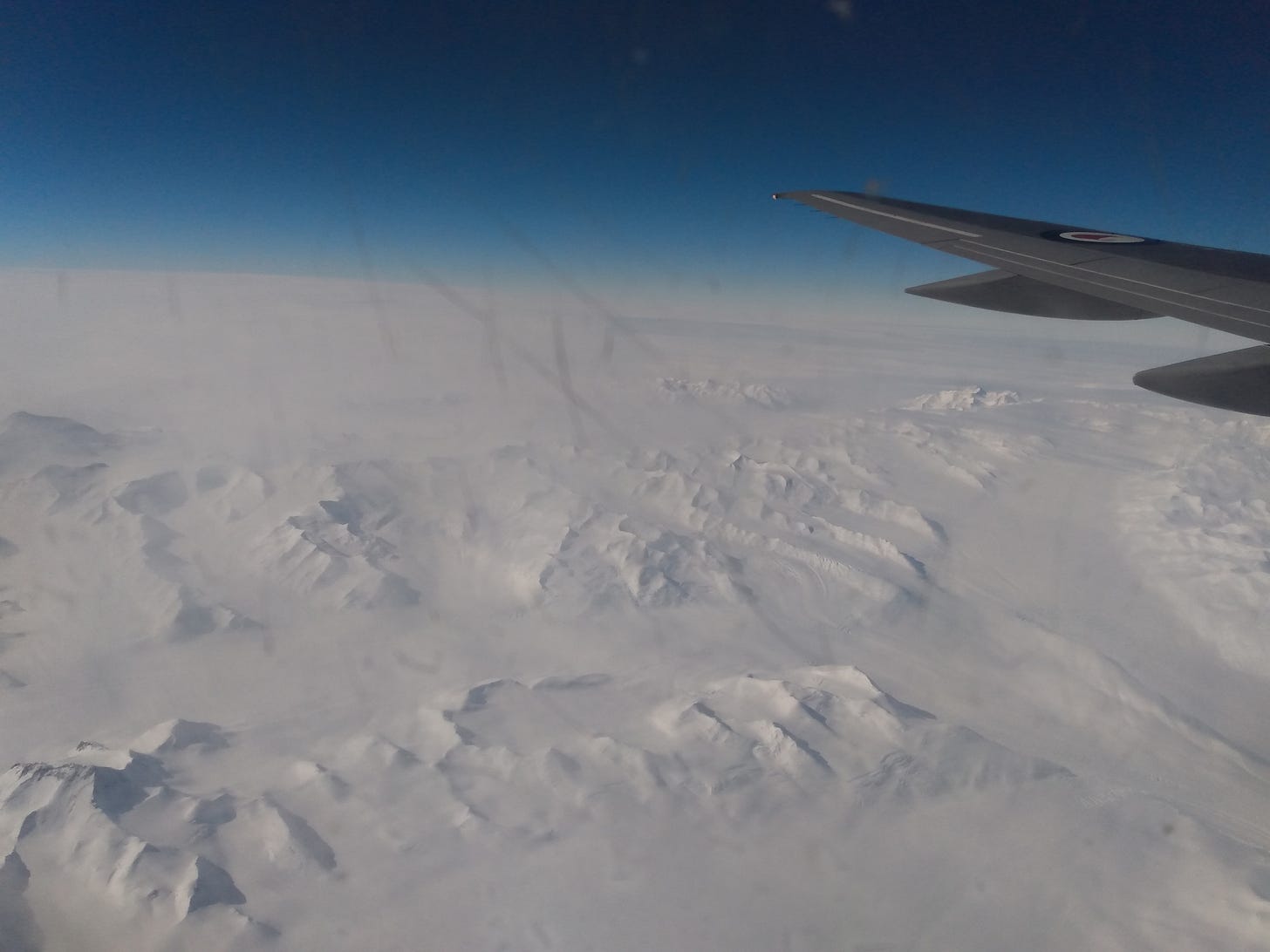

A week ago, as my plane climbed, New Zealand’s lush springtime disappeared beneath a gray overcast sky. Every time I return to Antarctica, my stomach sinks a little when plants disappear. But a moment later, the green world made a brief reappearance: mountain peaks poked through the sea of clouds like islands. I had another chance to say goodbye. All of this—disappearances, farewells—was to be expected. But very little about this deployment to Antarctica has felt normal.

Backstory: to get here, I flew to San Francisco, quarantined for four days in a hotel room alone at the airport and passed two covid tests, flew to New Zealand, quarantined for two weeks in a different hotel alone in MIQ—the government’s mandated quarantine for anyone entering the country—passed four more covid tests, was transferred to quarantine to at a different hotel (one that the U.S. Antarctic Program had to rent out entirely for 150 people) until my plane was ready to fly and Antarctica would allow us to land.

Normally, I fly to Christchurch in one go, have a few delay days to bask in New Zealand’s beauty and enact a few rituals: walking barefoot through grass, grocery shopping for whatever catches my eye and a picnic in the park afterwards, feeling my heart crumple as I watch poofball ducklings zig-zag across the surface of a pond. This time, we were limited to “yard time” in a cement courtyard surrounded by two chain-linked fences spaces six feet apart. We had to wear masks the whole time and social distance. Security cameras and New Zealand’s military personnel watched us, lest we attempt to escape. Thankfully, there was a small patch of anemic grass in the courtyard carpeting the roots of a lone tree.

Typically, I fly down on a C-17 by the U.S. Air Force, which is used mainly to fly cargo. This time we flew on a 757 flown by New Zealand’s Royal Air Force. We sat in normal seats and had a view out the window as we flew. I’ll admit: my insides were knotted. A C-17 can carry enough fuel to fly all the way to McMurdo Station, circle around the airfield for a while if sudden weather slams us, and return to New Zealand without needing to fuel. A 757 has a PSR, a “point of safe return,” which used to be called a “point of no return.” You can guess why the name was changed. About three-and-a-half hours into the flight, we can turn around and make it back to New Zealand, but once we pass PSR, we don’t have enough fuel to return and we are committed to landing in Antarctica no matter what storms she might toss at us. Seven or eight years ago, before my time, a 757 flew to McMurdo, and unexpected weather hit. The airfield was swallowed by fog. The plane circled the runway, waiting for a break and some visibility to land. Nothing. As the plane was about to run out of fuel, the pilots executed a blind landing with all the passengers on board in a braced position, ready for a crash. Emergency vehicles, firefighters, and medical staff were summoned to the airfield, prepared for the worst. The 757 landed safely. People were weeping. Some told me later that it was the scariest moment of their lives. After that freak incident, the 757 disappeared from the flying schedule for years. Now it’s back. Just after my plane passed PSR, we rumbled through turbulence for about twenty not-very-fun minutes as I questioned all the life decisions that led me to this point. But we made it. And it was a beautiful flight.

My reasons for agreeing to come here this year are complicated. A big part was that my partner, Nathan, wanted to experience the place I’d been talking about for years. I also sold myself on another season by reasoning that it would be nice to be somewhere “covid-free.” (One Antarctic station on the peninsula side of the continent had a case last summer). Covid isn’t here at McMurdo, the largest station on the continent. It isn’t here yet, but it permeates life here. We are free of covid, but we are not. Like so many places, McMurdo has been enveloped by the pandemic’s fog, which has moved in like unexpected weather. We’re landing as best as we can, using whatever skills and expertise we can, but blindly because there’s nothing else we can to do.

Our station has a code system to guide protocols depending on a number of factors. Without getting into the nitty-gritty, code green means we don’t need to social distance or wear masks and we can eat in the galley, our cafeteria. We should have a few periods of green this season. Code yellow means we must social distance and wear masks, there are occupancy limitations for rooms, and we cannot eat in the galley, but must bring our food elsewhere. Code red means there is a case or a suspected case on station and we must isolate in our rooms, except for essential personnel. Right now we are in code yellow, which presents even more logistical hurdles than the ones we already face working down here. Once a full week has passed since anyone new arrives on station (which will be tomorrow) we can move to code green. As you can guess, people are itching for it.

Everything I’m about to say is my own opinion and from my own experience and does not represent the National Science Foundation or USAP in any way. The station’s population right now is about 650 people. By December 1st, everyone on station is required to be fully vaccinated, which I think is needed. The protocols that guide us are necessary and I think many of us are doing our best, but due to the nature of living here, the structure of the buildings, and our basic human needs (like drinking water while working in a small office with nine other people and no ventilation for twelve-hour shifts, like I do), some of this feels like hygiene theater. It’s kindergarten-meets-submarine: tight quarters and varying degrees of cleanliness. Last year, the station was in “caretaker mode” with a skeleton population in the three-hundreds (a normal year we have a peak population of about 1,000 with about 1,400 total people cycling through). With over 600 now, it’s hard to truly mask and social distance well. We’re descending into a fog and hoping we land safely.

A few days after I got here, two untraceable covid cases popped up in Christchurch, the city we had just departed. Before August, New Zealand was, for the most part, a covid-free paradise. It’s still edenic, but delta has broken through the government’s careful barriers and could not be contained by strict lockdowns, so New Zealand has abandoned its zero-covid policy and is transitioning to living with the virus. All of our planes fly from New Zealand and the people who run operations and pilot them are in New Zealand, too. Those two islands were our buffer; now we don’t have that buffer.

Antarctica is a weird place to live and the pandemic has weirded life here even more. Besides navigating the pandemic’s fog, I’ve been setting up my dorm room, seeing people (and not being able to hug them), learning my new job as a supervisor, and remembering how to live in endless daylight (the sun has been above the horizon since I got here and will be until late February). But there have been pockets, reminders of what I love most about being here: inhabiting a dynamic living world and witnessing Earth’s raw power.

Even though we do not live in a normal civilization here, we can carry civilization—the built world—with us. Humans can be blind to the natural world. It’s a little harder to do that here, which I’m grateful for. A few days ago, there was a storm out on the Ross Ice Shelf, the Spain-sized glacier (and the largest piece of “floating ice” in the world) our airplanes land on. In my office I heard a driver report on the radio that a gust of wind blew his truck off the snow road (he was okay). The airfields were quickly shut down after that. That gust, for me, was a nudge, a little patch of blue sky in the fog, Antarctica tapping me on the shoulder.

Two days ago, Nathan and I strolled to Hut Point, a tiny peninsula just outside of station which holds a small hut from early visitors to Antarctica—“explorers” (not fond of the term anymore)—from over 100 years ago.

We passed other smiling walkers, whose faces were flush from the wind. We peered into the hut’s windows, examined a mummified seal, and gazed at the horizon towards the mountains from an eroded edge of a cliff. More arresting than the mountains: the blood-stained surface of the sea ice. Next to that red rose: a mamma Weddell seal and her newborn pup near its birthplace. The newborn wiggled next to its mom’s belly, likely breastfeeding; she laid still, then lifted her head to glance down at her little one.

Watching them interact in their nursery was the most grounded I’ve felt since I got here and a reminder to me that life goes on despite the pandemic, even here, and maybe especially here. Tomorrow, we go into green. Our masks can come off at 1700. We can hug, share meals, gather in groups again. I’m hoping for the best.

Steph

Hi Steph.

I’ve just joined this platform and come across your writings as I’m interested in Antarctica and am doing a short sort of overview course on the continent.

I’ve always wanted to go there and have about 80 early books on the Arctic and Antarctic.

When I think about what I would like to study the mind boggles as there are so many scientific modalities.

I have previously worked on harmful algae in Stewart island NZ where I live. So further study there is an option but it’s all so interesting.

One question I have is with all the millions of dollars spent on scientific research by many countries, how much of the results or outcomes can be acted upon immediately?

Are governments listening to scientists, as I imagine they fund a lot of research.

A large proportion of study is in predictions, but that’s no good unless action is taken now.

How have you found it having been down so many times. How far does your research reach past the scientific community?

Nga mihi

Craig

So glad you made it safely! You write so well and I love reading about your adventures. I cannot wait to hear about Nate's thoughts. You remain in my prayers. Stay safe!